Little Haiti

In 1925 the City of Miami annexed Lemon City, but the name lived on as Lemon City became a neighborhood within Miami. By the 1950s, Lemon City and the neighboring community to its north, Little River, had seen tremendous growth – both residential and commercial. And then the expressway system was built, taking away the area’s status as a crossroads and allowing the middle class to move further from the city center. With the end of segregation in the 1960s, African-Americans gained choices beyond the “colored towns” of Liberty City and Overtown, and many took up residence in the area.

At the same time, Francois Duvalier’s military dictatorship had seized total control of Haiti. Also known as Papa Doc, Duvalier used his military police force, the Tonton Macoutes, to terrorize the Haitian people into submission and 30,000 Haitians were killed by his government. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Haitian refugees began arriving in Miami and settling in the neighborhoods of Lemon City, Little River and Buena Vista. When Papa Doc Duvalier died in 1971, power was passed to his 19 year old son, Jean-Claude Duvalier, referred to often as Baby Doc. Under Jean-Claude’s rule, Haiti descended even deeper into economic and social despair.

Between 1977 and 1981, over 60,000 Haitians arrived by boat in South Florida, a large percentage of which joined the Haitian pioneers in Lemon City and Little River. Haitians arrived to find formidable obstacles and were, in general, not made to feel welcome in their new home. The U.S. government assisted Cubans as refugees from a political system, but rejected Haitians as economic refugees. There were no employment opportunities or social services for Kreyol-speaking Haitians, and like African-Americans, Haitians suffered racial discrimination. In addition to language obstacles and racial prejudices, Haitians had to deal with misconceptions, and often outright hostility, towards their practice of Vodou.

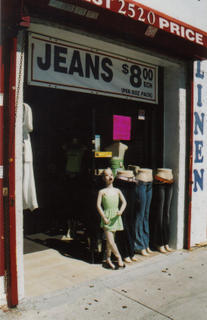

In spite of the challenges, Haitians continue to make their way to Miami, hoping for a better life. Haitians now make up around 10% of the population of Miami, and Little Haiti is now one of the largest neighborhoods in Miami. There are lots of Haitian and Caribbean restaurants, Haitian bookstores and botanicas (vodou shops). There are Haitian markets and salons and Haitian music stores selling kompa, rara and misik rasin style CDs. Amidst all of this, in true Miami fashion, there is an English punk bar called Churchill’s in the heart of Little Haiti. Mwe renmen Miami Ayisyen.